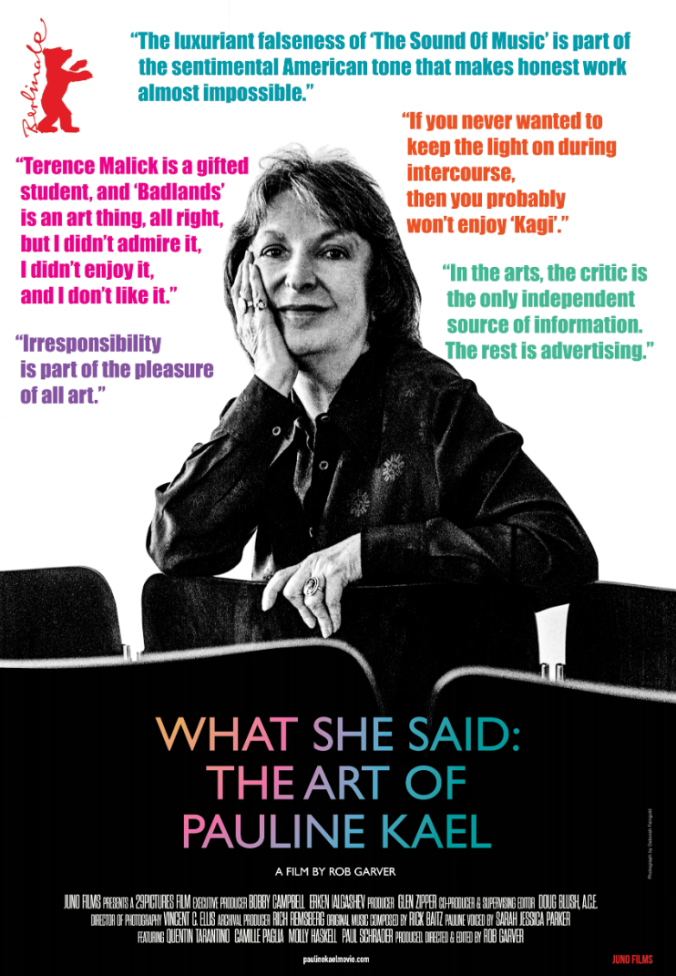

Pauline Kael is one of the most provocative and consequential film critics of the 20th century. I’d heard so much about her over the years and wanted to learn more, so I was quite happy when the documentary about her life — “What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael” — appeared on Amazon Prime.

Pauline Kael is one of the most provocative and consequential film critics of the 20th century. I’d heard so much about her over the years and wanted to learn more, so I was quite happy when the documentary about her life — “What She Said: The Art of Pauline Kael” — appeared on Amazon Prime.

In many ways, her life story was very different from what I expected. She faced significant personal challenges, including raising her daughter alone as a single mother while navigating a male-dominated industry. She was polarizing, fiercely opinionated, and enormously talented, which led to a remarkable career highlighted by her tenure at The New Yorker from 1968 to 1991, where she penned more than 400 reviews and essays.

Her writing style was distinctive: passionate, personal, and often provocative, blending sharp analysis with visceral emotional responses to films. She championed the “New Hollywood” era of the 1960s and 1970s, praising directors like Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Brian De Palma, while often taking aim at more established figures such as Stanley Kubrick. Right away, it was easy to like her as I learned more about her through this film. She was fearless, and in many ways I shared her taste in movies — especially the ones she admired.

Yet she could also be quite vicious in her criticism. While I respected that she never shied away from tearing into popular films, at times she seemed unable to appreciate genuinely great movies that simply didn’t align with her personal tastes.

Her review of “The Sound of Music” in McCall’s magazine was so scathing that it reportedly led to her firing. “The sugar-coated lie that people seem to want to eat … and this is the attitude that makes a critic feel that maybe it’s all hopeless. Why not just send the director, Robert Wise, a wire: ‘You win, I give up’?” Really? The film may not be for everyone, but as a musical, it’s undeniably brilliant.

Here’s a quote from her review of “Star Wars”: “One of the biggest box-office successes in movie history — probably because for young audiences it’s like getting a box of Cracker Jack that is all prizes. Written and directed by George Lucas, the film is enjoyable in its own terms, but it’s exhausting, too: like taking a pack of kids to the circus. There’s no breather in the picture, no lyricism; the only attempt at beauty is in the image of a double sunset. The loudness, the smash-and-grab editing, and the relentless pacing drive every idea out of your head, and even if you’ve been entertained, you may feel cheated of some dimension — a sense of wonder, perhaps. It’s an epic without a dream.”

Again, I admire her willingness to speak her mind, but she seems to have had a blind spot for anything that was simply fun for the masses. Plenty of serious critics have been able to appreciate this iconic film for what it is. It wasn’t addressed in the documentary but she hated “Raiders of the Lost Arc” as well.

Still, she loved Scorsese, Coppola, and De Palma, which made her a far more trusted voice when it came to edgier films, gritty dramas, and work that pushed boundaries.

Ultimately, her passion is what made her great. She rose to prominence during a period when film criticism was still largely polite, academic, or promotional — a tradition she had little patience for. Kael rejected detached objectivity in favor of visceral, emotional engagement. She wrote not as a scholar but as an impassioned viewer, insisting that movies should be felt as much as analyzed. Her reviews were personal, funny, combative, and often infuriating — qualities that made her both beloved and despised, sometimes at the same time.

By the end, this film made me want to seek out more of Pauline Kael’s writing — maybe even pick up a compilation of her reviews. I would recommend this documentary to anyone who loves film. Directed by Rob Garver and released in 2018, it works both as an accessible introduction for viewers unfamiliar with Kael and as a spirited reappraisal for those who understand just how profoundly she reshaped the language and purpose of film criticism in the latter half of the 20th century.